How many good land reports go unnoticed because there is too much information to choose from in the first place?

Bearing this in mind, Land Portal developed the Country Insights digest* - a reflection on some of the most important new articles and reports that aims to identify the most current points of discussion around land in different countries, distil key messages and points of debate, and offer you an entry point to learn more.

Periodically, one of our researchers will share her/his reading list and tell you why the selected pieces stand out in a sea of information.

In this first edition, Daniel Hayward brings you four articles that talk about customary land tenure and responsible agricultural investment. It’s a prelude to the 3rd Mekong Regional Land Forum with each article unfolding the topic of each session.

____________

* Update note: the Country Insights digest was re-branded in April 2022 to "What to Read digest" to better reflect its content

Daniel suggests...

On 26-27 May this year, the 3rd Mekong Regional Land Forum will be held online. Mekong Regional Land Governance (MRLG) is hosting the Forum, which the Land Portal Foundation is co-organizing.

The Forum will provide in-depth discussion and debate into land tenure security and community resource management, focused through the two main workstreams of MRLG, namely Customary Tenure and Responsible Agricultural Investment. Each day of the Forum will be dedicated to one of these workstreams, bringing together reform actors, community leaders and researchers.

To dig a bit deeper into the themes of the Forum, check my selection of four recently-published articles and my reflections on them:

- Persistence and Change in Customary Tenure Systems in Myanmar

- Governing Landscapes for Ecosystem Services: A Participatory Land-Use Scenario Development in the Northwest Montane Region of Vietnam

- The FPIC Principle Meets Land Struggles in Cambodia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea

- Pathways to human well-being in the context of land acquisitions in Lao PDR

The articles are a mix of academic papers and reports, all published since 2020. They are open-access and their case studies cover the four countries of focus for MRLG, namely Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Vietnam.

As a further port of call, I encourage you to consult our Country Portfolios for related lands: Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Attendance for the 3rd Mekong Land Forum is still possible, and those wanting to register, can do so here.

Persistence and Change in Customary Tenure Systems in Myanmar

By Christian Erni

The first day of the Forum addresses customary land tenure, with a particular focus on collective forest tenure rights. As a perfect introduction to understand the nature of customary systems, the 2021 report for MRLG by Christian Erni offers a review of reporting on the topic in Myanmar. (Read the full report)

There are more than 100 ethnic groups found within the country. The aim of the report is to bring greater clarity to the variety of customary tenure systems under which these groups operate. This understanding can help inform plans to draft and promulgate a National Land Law, allowing for the inclusion of measures to recognise and protect customary tenure. This objective has already been stated in the 2016 National Land Use Policy (NLUP), which acts as a precursor to the planned National Land Law.

Following work on customary tenure in Myanmar by Kirsten Ewers Andersen, three broad types of customary tenure can be identified:

- Systems with areas of shifting cultivation under communal tenure

- A mix of communal land (run by the community or wider ethnic group) and private plots (held by individuals or households)

- Systems where plots are held at the individual or household level, but which cannot be transferred to outsiders of the community

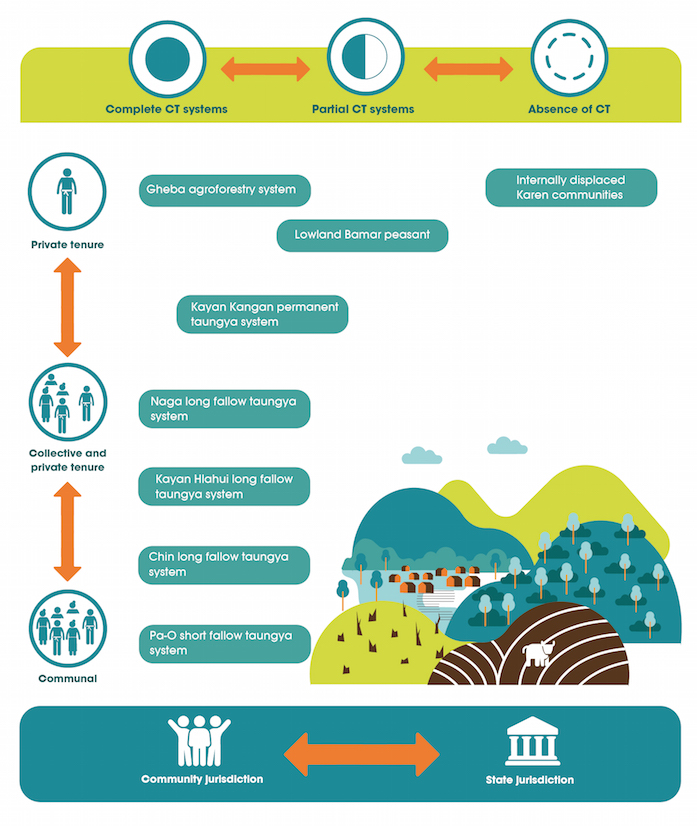

There are many factors determining what system a group follows, including environment, livelihood and land use system, demography, culture, history, and the wider socio-economic and political frame. Another frame of variation is the extent to which a customary tenure system presides over a community. Erni identifies three forms here:

- Absence of customary tenure

- Partial system – in areas where the State has administrative control, communities may have to enter into formal tenure-based schemes such as obtaining Land Use Certificates for farmland in lowland areas, or for Community Forestry Certificates. In these cases, the state system runs together with a maintenance of customary rules

- Complete system – where land is fully governed over local community rules

Figure 1: A Kayan Hlahui family prepare food and bamboo ties (by Christian Erni)

As an example, the indigenous Kayan Hlahui group, in Kayah State, practices shifting cultivation including paddy land, permanent agroforestry, and garden land under individual ownership (Figure 1). Most forest areas are owned by clans, but all villagers have access and usage rights. Through the report framework, the customary system is complete, showing a mix of communal land and individual plots.

Using this framework, Erni assembles a typology of customary tenure systems, bringing in a number of case examples (Figure 2). However, he makes the vital assertion that such systems are far from static, and under the influence of changing socio-economic dynamics. In particular, he highlights the movement from shifting cultivation to commercial forms of agriculture, including the cultivation of cash crops and forms of agroforestry.

Figure 2: A customary tenure continuum (by MRLG/Christian Erni)

For example, the Gheba are an ethnic group based in Kayin State who have moved from subsistence farming through shifting cultivation to commercial agroforestry with little food production (Figure 3). This has resulted in the individualisation of much land, and unforeseen consequences such as distress sales through food shortages. There is a continuing debate on the entry into agricultural markets, and its impacts upon peripheral rural communities. We will see a further example in the following article with a case study in northwest Vietnam, while Nanthavong et al. assert that such a transition is needed for the development of rural livelihoods.

Figure 3: A Gheba village located within a forest in Kayin State (by Christian Erni)

The report raises major concerns as to the limited recognition given to customary tenure in national law and policy. In the gazetting of forests, local communities have frequently been left out of decision-making processes. With the 2018 Forestry Law potentially allowing private sector investment into forest areas too, there are fears that this could further marginalise local users dependent on these areas for their livelihoods. The law allows for co-management schemes as Community Forestry, but fails to include existing customary tenure systems as a mechanism to help manage forests. All the more reason to push for clear measures in a new National Land Law.

Governing Landscapes for Ecosystem Services: A Participatory Land-Use Scenario Development in the Northwest Montane Region of Vietnam

By Trong Hoan Do, Tan Phuong Vu, Delia Catacutan and Van Truong Nguyen

Customary tenure arrangements are often seen as running counter to a state-based management system of land that both look to exploit the economic potential of natural resources within a country, as well as seek protections for the conservation of these resources. In actuality, customary tenure can be a vital factor in the creation of co-management systems that support local livelihoods as well as the sustainability of ecological systems. (Read the full report)

As an example, the academic article by Do et al. takes a close look at the technocratic process of land-use planning and how it can support ecosystem services. It shows that community and state-based environmental claims on land are not mutually exclusive, and that the role of communities, using their customary tenure practices in land ownership and use, is integral to the success of climate-related and other environmental programmes. In particular, the article shows how local communities are needed for Vietnam to fulfil its NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) as part of climate goals set up under the 2016 Paris Agreement.

The case study presented here looks at Na Nhan commune in Dien Bien Province, northwest Vietnam (Figure 4). The area is described as containing a forest-agriculture mosaic landscape. To investigate the potential of community involvement in land-use planning, the study team applied a Participatory Land-Use Planning for Multiple Ecosystem Services (LUMENS) framework. There are four steps involved here:

- Compile local land-use issues and perspectives on current land-use plans

- Estimate greenhouse gas emissions and sequestration from all land-use change. In this case, a ten-year period was covered from 2005 to 2015

- Through a participatory process, develop a baseline and LUMENS scenarios which adopt land-use interventions as preferred by local stakeholders

- Assess the impacts of the land-use scenarios upon the landscape’s ecosystem services with stakeholder feedback

Figure 4: Terraced Crops & River, Dien Bien Province Vietnam (by Adam Cohn)

What is clear to see here is the importance of the inclusion of a community voice to verify processes of land-use change, discuss drivers of this change and help create a vision to secure multiple ecosystem services. Indeed, the process provides an opportunity to look beyond formal classification systems for land-use, and look at ground-level realities, including the presence of shifting cultivation practices.

However, there is a problem of incorporating customary tenure practices, particularly in the management of forest areas. While all residential and agricultural areas were clearly allocated under a state land administration, for forest areas, land-use rights (via the formal Red Book) were only allocated for forestry purposes alone. Although customary cultivation in forest areas was known and tolerated by local government authorities, they do not wish to provide legal recognition here. One option from the consultation is for local communities to convert shifting cultivation areas and home gardens into mixed fruit-tree systems, and intensify home gardens incorporating principles of agroforestry. In a best-case scenario, an approved forest use system would acknowledge local practices and bring them into formal recognition so that they can contribute to management strategies.

Simply put, the recognition of customary tenure can be to the benefit of all. As well as participatory programmes from the bottom-up, there is a need to recognise such systems from the top-down. Tied into agroforestry practices, this can be a contributory practice for the use of degraded forest land, bringing economic and ecological benefits to the area. Finally, there is great worth in such consensus-building exercises chipping away at walls of mistrust and antagonism to consolidate common ground.

The FPIC Principle Meets Land Struggles in Cambodia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea

By Colin Filer, Sango Mahanty and Lesley Potter

The second day of the Forum looks at Responsible Agricultural Investment, with a focus on how local user voices are included in decisions on the capitalisation of land. One way to do this is through Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), which is the topic of the first session in the day. (Read the full report)

The academic paper by Filer, Mahanty and Potter looks at how the principles of FPIC could be applied and used to protect the land rights of affected groups, in the face of land acquisitions for investment projects. As a conceptual frame, the authors reiterate Karl Polanyi’s assertion that land cannot be reduced to a singular function as a commodity, thereby stripping it of vital environmental, social and cultural functions. In this way FPIC represents a form of protection to acknowledge social and cultural rights contributing to the identity of local user groups, as well as providing them with an economic base. Polanyi's conceptual frame underpins all the articles presented in this digest.

The paper compares the use of FPIC in three countries, namely Cambodia, Indonesia, and Papua New Papua, using the extensive field experience of the three authors. In the case of Cambodia, the government voted to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which contains the provision to implement FPIC, in 2007. Yet there has been no qualified insertion of FPIC principles into national law and policy. For a more detailed perspective, the paper presents two case studies from Mondulkiri Province in northeast Cambodia:

for the dispute settlement

over the Socfinrubber project

by Sothath Ngo)

- Socfin Rubber Project

In 2007-8, the Cambodian government allocated two Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) to the French company Socfin, in order to set up a rubber plantation. There was no legal obligation to follow formal FPIC principles and engage with a local indigenous Bunong community, who lost their lands through the investment. Engagement only took place following persistent protests against the venture by the affected community, in particular relating to the burning down of burial sites during initial forest clearances.

A network of organisations advocated for an appropriate compensation settlement, and an investigation by the French-based International Federation for Human Rights ruled that the project had violated the UN Global Compact and the UN Framework and Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, as well as the OECD Guidelines.

As a postscript to the case study presentation, after five years of mediation, on Monday 10th August 2020, company and community signed an agreement recognising 500 hectares of communal land, paving the way for it to be formally registered (Figure 5).

- Voluntary carbon markets

Taking place at Seima Protected Forest (Figure 6), the implementation of a voluntary carbon market project should in principle engage FPIC in order to satisfy the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and also Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards (CCBS). However, in reality, the exercise of performing FPIC was little more than a box-ticking exercise of collecting thumbprints and fulfilling a signing ceremony, without properly informing the local community and allowing them meaningful dialogue.

Looking at the examples from Cambodia, the first case shows how a transnational network of community and advocacy groups is increasingly bringing land grievances into the public domain. For foreign investors to access global markets, problems may emerge when operating in countries where FPIC compliance is weak. In this sense, a lack of state support in Cambodia for mechanisms like FPIC could undermine investor confidence.

Figure 6: Mixed bamboo and semi-evergreen forest in Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary, Cambodia (by Pygathrix nigripes)

The second case shows how there is not always a guarantee that FPIC will be stringently applied. This demonstrates that Responsible Agricultural Investment is not something that is simply just performed, but requires the support of national policy and well-trained capacity. Indeed, even with professional mediators, the Socfin dispute took five years to resolve, a process which could have been avoided with due diligence from the outset of the project.

Pathways to human well-being in the context of land acquisitions in Lao PDR

By Vong Nanhthavong, Christoph Oberlack, Cornelia Hett, Peter Messerli, and Michael Epprecht

There are many challenges as to how investors may achieve a return for their venture, but without cost to the livelihoods of local land users, including their ability to maintain customary tenure practices, and at the expense to the environment. To give context to the impact of investment on human well-being, a new paper by Nanhthavong et al. analyses data on 176 land acquisitions in Lao PDR to assess their impact on 294 affected villages. The acquisitions in question here focus on land concessions for agricultural ventures. (Read the full report)

The analysis considers three key indicators of well-being outcomes (food security status, income, and livestock production) and six key indicators of well-being resources (access to farmland, NTFPs and wild animals, timber and firewood, water for agricultural production, technology or skills transfer, and road access improvement).

Figure 7: Eucalyptus plantation in Lao PDR (by Chris Lang)

The impact of each concession was measured in terms of increase, decrease, or no change for each indicator. This was based largely on interviews with affected villagers from the concessions. As a result, four patterns of changes could be applied to the 294 villages, bringing together findings for each indicator:

- Improved or enhanced

- Unchanged

- Adverse outcome

- Trade-offs between indicators

Of the 4 patterns, 37% of the 294 affected villages witnessed a trade-off between well-being outcomes (e.g. decrease in food security but increase in income). 31% of villages witnessed an overall adverse outcome while 24% saw an enhanced outcome. For well-being resources, 68% faced losses in one or more resource types. No village witnessed a consistent improvement. From the results, the authors highlight five processes which help explain why human well-being has a better outcome in some villages rather than others. The two most relevant processes in relation to the themes of the Forum are:

- Shifting access to land and natural resources - the displacement of villagers nearly always results in adverse impacts, with the new land not acting as a suitable replacement in terms of quality, size, or location. Having a land title provides villagers with a legal status, improving their ability to negotiate deals or protect their interests. However, many concessions take place in areas where titling has not taken place. Indeed, the paper recommends that concessions do not take place in areas with low land tenure security.

- Commercialisation of Agriculture – Moving towards commercialised agriculture and livestock production is the best means to increase household incomes. However, this is not contingent on large-scale acquisitions, such as concessions, and so there are other ways of involving smallholder farmers to help share benefits and maximise income gains.

This final point is vital to inform discussions on Responsible Agricultural Investment. In the last ten years both the Lao and Cambodian governments have announced moratoria on new land concessions, questioning the worth of the model which has not provided the expected economic return. Indeed, the paper here concludes that land acquisitions as they stand in Lao PDR are on the whole ineffective as a means towards rural development. There is much interest in the region in finding alternative ways to capitalise land, such as through contract farming. This provides an opportunity to lobby for the inclusion of and benefit-sharing with smallholders and the rural poor.

Nanhthavong et al. suggest that small-scale deals can result in positive well-being outcomes for local communities, even if the window to enable a successful process is small. A key to success is the protection of land rights. Yet as Christian Erni reflects in the MLRG report, legal provisions in Myanmar in the context of capitalisation of land have failed to acknowledge the occupation of much land by local users under customary tenure rules. By changing this approach, not only might local livelihoods benefit from investment projects in rural land areas, but customary tenure practices can also be aligned with environmentally sustainable management schemes.

Figure 8: Clearing jungle for more profitable rubber trees - Muang Sing, Lao PDR (by Houston Marsh)