Who walks away from fertile agricultural land available to lease for as little as $1 per year per hectare? Recent reports indicate international investors are doing just that across sub-Saharan Africa.

Investors began pouring into the continent with pockets full of cash and get-rich-quick dreams built on cheap, fertile, and readily available land during the food crisis of 2007 and 2008. What followed were heart-wrenching stories of conflict and displacement.

Now, some are calling these massive land grabs a myth.

“A mounting body of evidence points to a recurring pattern in which insecure property rights and political disputes cause initially euphoric global investors to cancel proposed deals or walk away from farming projects across the continent,” writes Till Bruckner in Foreign Policy.

If true (still a big if), this would be cause for some relief, but should also serve as a wakeup call.

Indeed, if well-funded, well-connected, and well-educated investors are walking away from African land because of insecure property rights, how can we expect underfunded, poorly connected (literally and figuratively), and poorly educated African farmers to make a go of it?

Aligning Incentives

Ironically, it appears global investors are learning what African smallholders have known for years: without secure legal rights to land, long-term productivity-enhancing investments are a major risk. Planting an orchard, building irrigation, or terracing land held insecurely makes about as much economic sense as changing the oil on a rental car.

Further, without secure rights to land, attracting financing and other services necessary for efficient farming is almost impossible.

Smallholder farmers are subject to the same math as investors

The trepidation with which investors are increasingly approaching land deals should demonstrate the substantial constraints insecure land rights place on tens of millions of African smallholders whose yields and incomes are stunted generation after generation by the legal limbo under which they live and farm.

Currently, though land is the most important and valuable asset across rural African societies, 90 percent of rural land is undocumented, according to World Bank estimates. That leaves farmers without the security, stability, and long-term commitment to the land that secure and documented land rights can bring.

This is particularly true for women farmers (and 60 percent of Africa’s women work in agriculture), who often access land through the grace of male relatives, an arrangement that becomes increasingly insecure as demands for land grow and customary safeguards are challenged.

There is a wealth of research in Africa and beyond that shows farmers will invest more of their time and savings in long-term improvements to their land that can increase production, reduce soil erosion, improve soil quality, and protect trees when they have secure land rights. These “climate smart” investments (see this infographic) serve both farmers and society.

When women have secure rights to land those benefits ripple even wider and can result in improved family nutrition, improved status for women, and improved family savings.

Africa’s smallholder farmers are subject to the same math investors are. There is a disincentive to long-term productivity enhancing investments. Farmers know improvements to the land, whether it be in the form of improved irrigation, terracing, or crop varieties, actually makes the land more attractive to neighbors, relatives, or government officials who might use their power, connections, or wealth to claim it.

Change on the Horizon? Maybe

Africa has no shortage of home-grown motivated, eager, and hardworking farmers. It does have a shortage of legal infrastructure and institutions that allow smallholder farmers to invest with the confidence that they will be the ones to reap the fruits of their labor.

There are signs that world leaders are waking up to this crisis.

The Voluntary Guidelines adopted by the Committee on World Food Security in 2012 aim to help governments safeguard the rights of people to own or access land.

The inclusion of land tenure under three of the new Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations last year will also help us gain traction on this. A land target under the poverty alleviation goal, end hunger goal, and gender equality goal will help spotlight the need and measure progress.

There are a number of countries in Africa that are making important advances in strengthening tenure rights, including Rwanda, Ethiopia, and Uganda. Donors like the UK Department for International Development, U.S. Agency for International Development, UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Omidyar Network, and Ford Foundation are providing much needed support for these critical efforts. And companies like Coca Cola, Illovo, and Nestle are recognizing insecure land rights as a threat to their reputation (see Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign) and the productivity of their supply chains

Such efforts should be expanded and supported.

If indeed we are seeing a pullback from large scale corporate land investments in Africa, this is certainly cause for relief. But it should equally serve as profound attestation of one of the biggest barriers holding back more equitable, bottom-up development on the continent.

Chris Jochnick is CEO of Landesa, a global non-profit that works to strengthen land rights for women, men, and communities.

Sources: The Brookings Institution, Foreign Policy, Landesa, Oxfam, Prosterman et al. (2009), UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

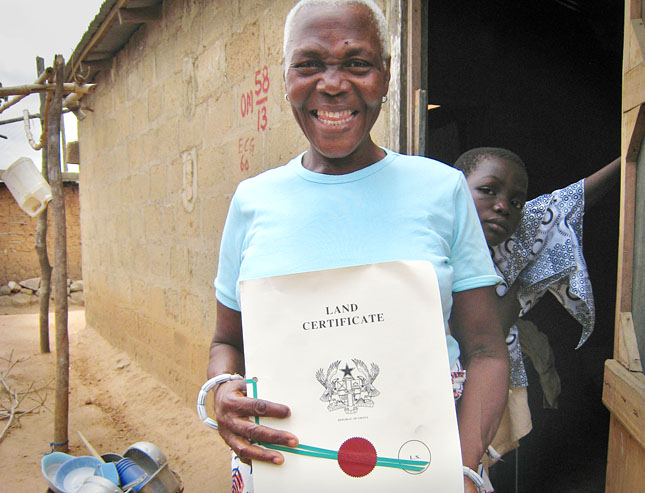

Photo Credit: A woman in Ghana displays the certificate to her land, used with permission courtesy of Deborah Espinosa/Landesa.