The data revolution – characterised by the transition to big data, open data and new digital data infrastructures [1] – is projected to make an astonishing 44 billion terabytes of digital data and information available by the end of 2020 [2]. Despite this plethora of information now available to us, about 1 billion people in 140 countries still feel insecure about their land and property rights [3].

A study commissioned by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH The Role of Open Data in Fighting Land Corruption: Evidence, Opportunities and Challenges, January 2021, has arrived at new insights into the current data revolution and the important role it can play in attaining sustainable land governance. In particular, it focuses on the impacts achieved by open data information systems and transparency initiatives on the various forms of corruption that affect the land sector.

This study revolves around two concepts, namely open data and corruption. It explores their interaction and repercussions in the specific field of land governance. Indeed, new technologies such as linked open data and blockchain – together with an ever-growing data, knowledge and information base – offer an unprecedented opportunity to promote transparency, fight corruption and to inform decision and policy-making [4, 5]. However, with new opportunities also come new challenges, and a series of barriers continue to limit the adoption of innovation in information and communication technology (ICT). This undermines their success as anti-corruption tools [6, 7] in the land sector and beyond.

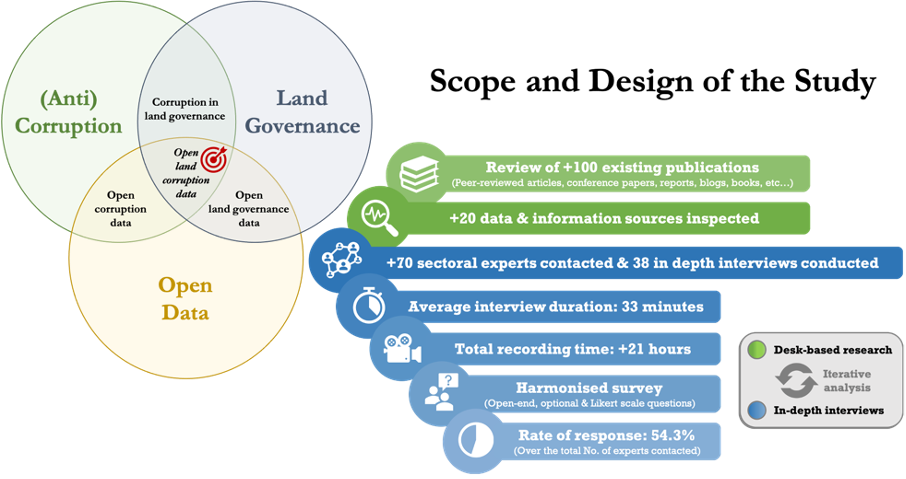

Figure 1 - Scope and design of the study

Open data, land governance and the many faces of land corruption

According to the Open Definition, open data are data that:

anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness.

Despite the emphasis put on the social benefits deriving from open data, it is usually harder to pinpoint direct and indirect impacts of open data and ICTs in terms of their effects on increased transparency, accountability and participation. When it comes to open data in the land sector, it must be noted that there are a number of relevant, yet competing, data and information needs. For instance, for land ownership data there are at least 4 different domains of information that need to be considered [8], namely:

i) cadastres and land registries

ii) land concessions, large- scale land acquisitions and long-term leases

iii) land use and land use change

iv) land governance and institutions.

Despite the increase of information sources in recent years, land ownership data are rarely open and accessible. Figure 2, which is based on data from the 4th edition of the Open Data Barometer (ODB), provides evidence to support this claim.

Figure 2 - Availability of open land ownership data based on the Open Data Barometer (2016, 4th ed.)

It is this lack of transparency and openness in land information systems, together with the presence of overlapping and sometimes conflicting tenure systems in many countries around the world, which creates a perfect environment for corruption to thrive in many areas related to land governance.

Corruption typically bears a wide range of costs on individuals and on society as a whole. Furthermore, land corruption is a sectoral form of corruption that affects both urban and rural areas, and disproportionately affects vulnerable and marginal groups in society. Some of the negative implications of land corruption are recurrent:

- Land corruption can reduce the ability of small-scale farmers to increase agricultural productivity,

- It can contribute to restrict access to land for specific groups, especially for those who rely on this vital resource for their livelihood;

- It can contribute to money laundering;

- It can exacerbate gender inequalities, favouring gendered forms of discrimination in land and property inheritance;

- It can lead to fundamental human rights violations, such as forced evictions;

- Finally, land corruption may lead to social unrest, land conflicts and land disputes across the world.

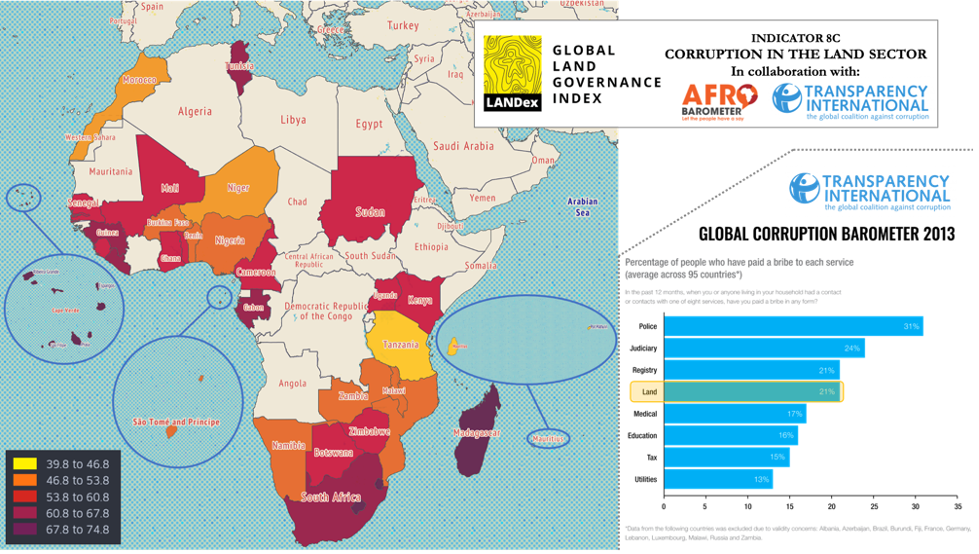

Figure 3 – Map: Distribution of perceived levels of land corruption in Africa, based on Landex indicator 8c – Corruption in the land sector (International Land Coalition, 2020), where higher values reflect higher levels of perceived land corruption; bar chart – reproduced from the 2013 Global Corruption Barometer and in collaboration with the Afrobarometer (Transparency International, 2013, p. 11).

Using open data and transparency initiatives as anti-corruption tool in the land sector: Areas of Consensus

The research identified three areas of general consensus:

- There is not enough evidence to measure the impact of open land information systems and to track their anti-corruption achievements. Open land data initiatives must establish a baseline against which progress and impact can be measured.

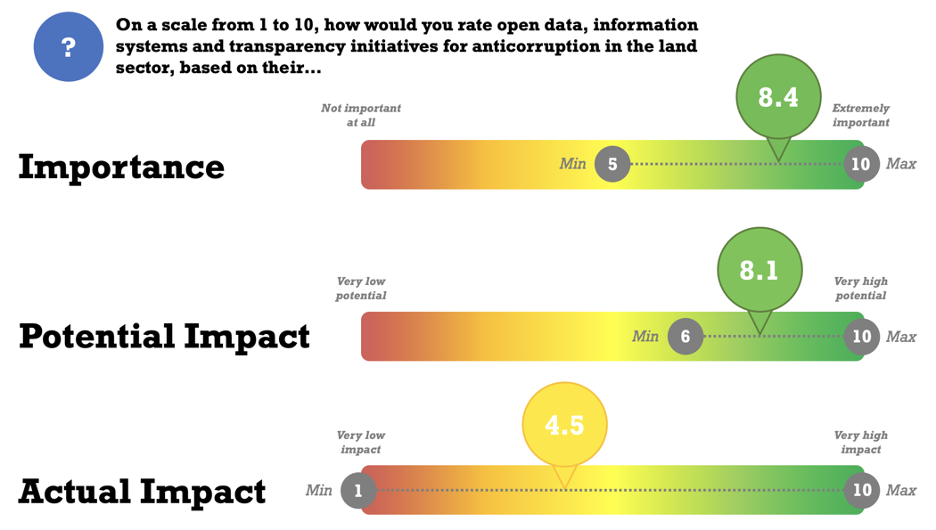

- As shown in Figure 4, almost unanimously, our global panel of experts recognises the importance of open data and transparency initiatives as anti-corruption tools in the land sector. However, a significant gap remains between the potential and the actual impact of these initiatives, suggesting untapped potential and underlining the need for improved monitoring and evaluation.

- The success of open data and information systems depends on how well they are designed and implemented, and the presence of various preconditions. Technical preconditions include common data standards, interoperability of sources. Institutional preconditions include the political will to use open access land information for anti-corruption.

Figure 4 – Open data and information as anti-corruption tools in the land sector: measuring experts’ perceptions

Using open data and transparency initiatives as anti-corruption tool in the land sector: Trade-offs, disagreements and potential solutions

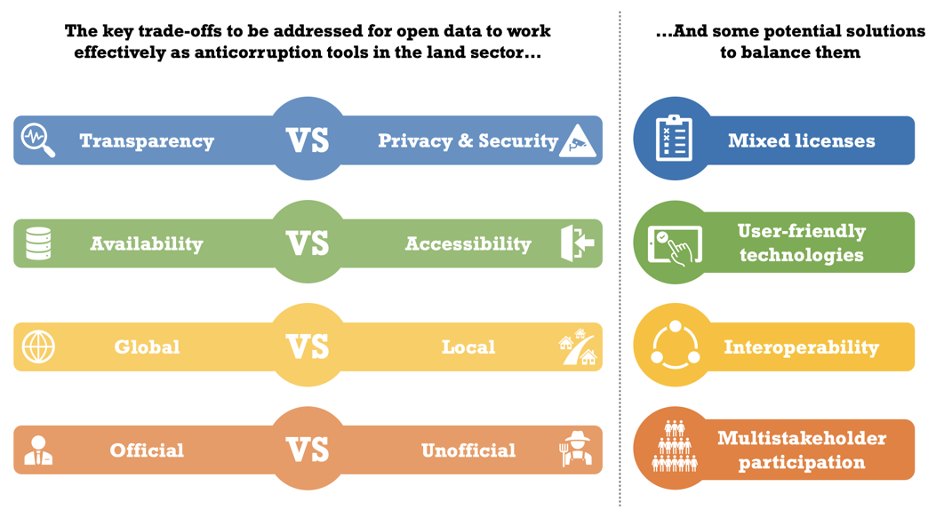

While there is generalised consensus on some aspects, the analysis also revealed that there are 4 fundamental issues that can be well described as trade-offs:

- Transparency VS Privacy: Land information systems typically contain sensitive personal and business information, creating tension between the importance of transparency and legitimate privacy concerns.

- Availability VS Accessibility: Open data systems are able to make the vast (ever-growing) quantities of land records available to everyone. They must also ensure this complex and detailed information is equally accessible to different users with diverse needs and levels of expertise.

- Global VS Local: The fight against corruption requires global coordination and concerted cross-border action. Land corruption is also strongly influenced by many factors at the local/national level, which require locally-specific and appropriate solutions.

- Official VS Unofficial: Gaps between official and unofficial sources of land data require multi-stakeholder participation to legitimise unofficial sources, encourage uptake by public authorities and provide incentives to open up existing but restricted official sources.

Figure 5 – Key trade-offs and potential way to balance them

Key recommendations

Using an iterative analytical process that combined desk-based research with in-depth interviews among a panel of sectoral experts, this report examined the current information ecosystem at the intersection of open data, land governance and (anti)corruption. Our analysis revealed overwhelming support for the use of open data as an anti-corruption tool in the land sector, but it also found strong evidence for the existence of a high degree of untapped potential. Building greater consensus on open land data and information initiatives, as well as producing further compelling evidence to demonstrate their impact in eradicating land corruption are crucial elements for unlocking this potential.

The study provides a series of recommendations to increase the impact of open data as an anti-corruption tool in the land sector:

- Ensure all land data is ‘open by default’. The land sector needs to reject the ‘closed by default’ approach that has dominated for too long, and embrace the open data principles and standards needed to increase transparency and achieve anti-corruption goals.

- Create an open land data ecosystem. Open data initiatives require a functional information environment including an enabling legal framework and political will.

- Engage multiple stakeholders throughout. The full potential of open data systems can only be realised with the active participation of different user groups at all stages of the data life cycle: from inception through to using data for accountability and anti-corruption purposes.

- Ensure women and disadvantaged groups participate. Those currently on the margins of land information systems must not only be given access to the data, but also contribute to the creation and evolution of the ecosystem itself.

- Scale up monitoring and evaluation. New and existing initiatives must increase their monitoring and evaluation efforts and improve their impact assessments, helping to make the case for interventions at the intersection between open data, land governance and anti-corruption.

- Speak with one voice. A simple, powerful, and evidence-based advocacy message from initiatives around the world is necessary to promote open data in the fight against land corruption.

Open data and transparency initiatives are not magic bullets against land corruption, but it remains very hard to imagine corruption-free and sustainable land governance without an open data ecosystem that enables the free flow and reuse of relevant data and information.

References

- Kitchin, R. (2014): The Data Revolution Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences. Los Angeles, London, New delhi: SAGE.

- Desjardin, J. (2019): How much data is generated each day? | World Economic Forum, World Economic Forum - WEF. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/04/how-much-data-is-generated-each-day-cf4bddf29f/ (Accessed: 14 August 2020).

- Prindex (2020): Comparative Report - A global assessment of perceived tenure security from 140 countries. London.

- De Maria, M. and Sato, R. (2019) Achieving the SDGs and other global commitments on land in the ‘age of data’, Land Portal’s Data Stories. Available at: https://landportal.org/blog-post/2019/06/achieving-sdgs-and-other-global-commitments-land-’age-data’ (Accessed: 25 August 2020).

- Kossow, N. (2020): The potential of distributed ledger technologies in the fight against corruption. Bonn and Eschborn. Available at: https://www.giz.de/de/downloads/Blockchain_Anticorruption-2020.pdf (Accessed: 30 April 2020).

- Conradie, P. and Choenni, S. (2014): On the barriers for local government releasing open data. Government Information Quarterly, 31, pp. 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2014.01.003.

- Berends, J., Carrara, W. and Vollers, H. (2017) Analytical Report 5: Barriers in working with Open Data. Luxenbourg. Doi: 10.2830/88151.

- Davies, T. and Chattapadhyay, S. (2019) ‘Open Data and Land Ownership’, in Davies, T. et al. (eds) The State of Open Data: Histories and Horizons. Cape Town and Ottawa: African Minds and International Development Research Centre, pp. 181–195. Doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.2677839.

- Fleming, S. (2019) How bad is the global corruption problem? | World Economic Forum, World Economic Forum articles. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/corruption-global-problem-statistics-cost/ (Accessed: 2 September 2020).