Malcolm Childress visited Honduras in April as part of a fact-finding and speaking delegation sponsored by the US State Department.

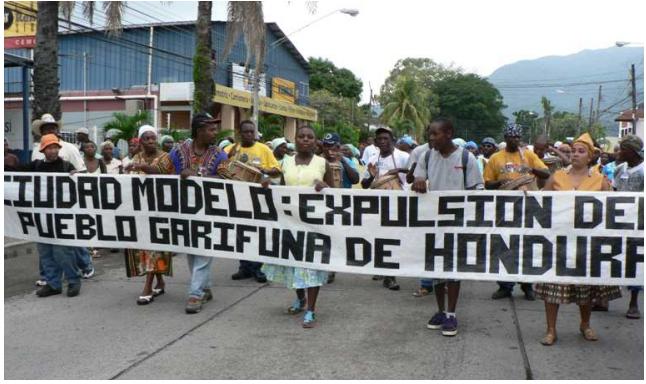

On the northern coast of Honduras, palm forests give way to white sands, blue seas and one of the world’s most spectacular coral reefs. But, in a story that will be familiar to observers of land rights worldwide, that beauty has brought developers eager to build, and conflict around the ownership of land occupied and claimed by longstanding Garifuna communities.

Conflicts over land are part of what has made Honduras a country characterized by exceptionally high levels of violence. The 2016 murder of the land rights activist Berta Caceres is the case which has received the most notoriety in international media, but conflicts are widespread. Not far from the north coast in the Aguan Valley 140 people were killed in land rights-related violence in the three years to 2014.

Honduras is also one of the countries in which Prindex is currently collecting new data on citizens’ perceptions of the security of their rights. For us, this is more than just a research project. When we publish in October, we want to contribute to processes which reduce and prevent conflict over property rights such as those affecting communities of the northern coast, by situating their struggles for the first time in a truly international study of citizens’ perceptions of land rights, calling international and national attention to the issues in a new way.

I heard from people on the northern coast and Bay Islands who had been threatened, and whose loved ones have been subject to violence related to land conflicts.

In several cases, coastal areas where traditional villagers have farmed, foraged and fished for generations have been turned into condos or golf courses, or fenced off pending new development. Some residents have left, migrating to the US or big cities, and many who have remained express a deep sense of deprivation of part of their livelihood and heritage.

Elsewhere in the country, mining, agribusiness and hydroelectric projects have driven similar conflicts.

The activists I met with on the north coast frequently cited the decisions of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights that were handed down in 2015 concerning three of these communities to restore their ancestral land as definitive support for their claims. But implementation of these decisions has yet to become evident. The government insists that these decisions are being implemented and that it is currently undertaking valuation of private claims in the affected areas to make compensation. (Our data includes questions on the perceived effectiveness of courts and government to enforce land rights laws.)

What stands out to me is the isolation of these communities in their struggle to resolve their claims, and the lack of visibility of their story within national debate and consciousness. The Garifuna communities and the Bay Islands felt a long way from the front pages. There was a tremendous frustration that, people told me, the government wasn’t listening.

The role of Prindex is to be part of redressing that, pushing land rights further up the political agenda, and showing that there is global as well as national interest. As we conduct future rounds of our survey, we will know more about which countries are making progress, and which are standing still.

I believe that’s why there has been so much interest in Prindex from policymakers who want to move the land conversation forward, as well as from civil society. There is reason for cautious optimism. The global land rights community is stronger and more ambitious than ever. In Prindex, for the first time, it will have a dataset to match that ambition, and provide a foundation for efforts to deliver security of land tenure and property rights worldwide.