Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia and many other countries are calling for political, civil and economic rights, recognition of their right to exist, as well as socio-ecological sovereignty over their territories. These issues were the focus of discussion at the commemoration of the 2024 edition of the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples organised by a coalition of civil society organisations in the Central Kalimantan province of Indonesia. The day aimed to showcase Indigenous culture and raise awareness about the political and policy challenges confronting Indigenous communities in the region. The event included a panel discussion on the state of Indigenous rights, traditional dances from a Dayak dance troupe, poetry performances and multiple concerts by reggae, rock and rap groups whose songs integrate indigenous consciousness.

imploring young people to not lose heart and keep

protecting the forest. Credit: Jahrul Husin.

2024 International Day for the World's Indigenous Peoples.

Credit: Jahrul Husin.

Squeezing Indigenous Peoples out of their territories

Worldwide, the territories of Indigenous Peoples are being squeezed by extractive sectors such as agribusiness, mining, and logging. And recent research suggests that Indigenous territories could become even more fragmented due to increased mining for minerals “necessary” for the green energy transition. In the way most of these large-scale extractive projects are implemented, Indigenous Peoples’ perspectives are hardly heard, and their right to say no is rarely taken into account. These land-hungry sectors expand into Indigenous territories and sometimes cause violent conflict, loss and permanent damage to landscape, cultures, languages, ancestral practices, and identities.

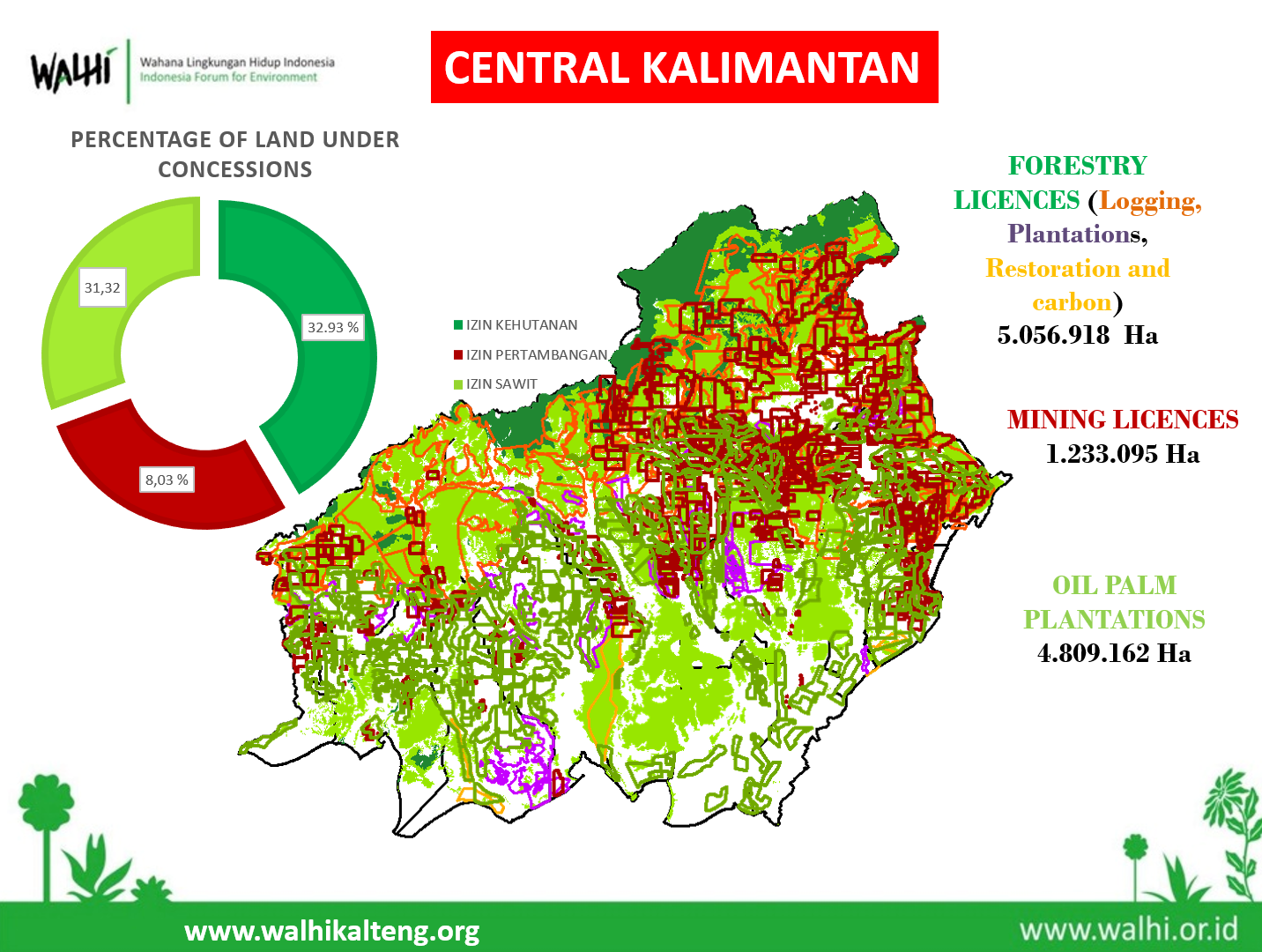

In Central Kalimantan, which has a land mass of a little over 15 million hectares, at least 11 million Ha have been granted to investors – mainly for oil palm, coal mining and industrial logging – according to analysis conducted by WALHI Central Kalimantan (see figure 1). This represents 72% of the entire province. During the festival’s panel discussion, WALHI’s Director, Bayu Herinata who is a member of the Dayak Ngaju tribe, pointed out that in contrast, just 305,000 Ha have been registered by the government as Indigenous territory—called Adat in Indonesian law. Of those 305,000 a mere 68,000 Ha is registered as Adat forest. This is a tiny fraction of the historical living spaces of Central Kalimantan’s Adat communities, and insufficient to ensure their survival and flourishing.

The application process for legal recognition of Adat status, includingthe right to Adat territories, often produces unfair and arbitrary results. Herlianto, a member of the Save Our Borneo organisation supported an Adat community to file an application for its forest. Even though the community’s customary forest covered 16,000 Ha, they were only granted 5,000 Ha.

In some cases, registration has not even saved Adat territories from encroachment by large-scale investors. Afandi, Director of the YBBI organisation labelled this phenomenon “government recognition without rights.” He’s calling for enhanced legal protections for “ethno-agro-forest Adat communities” that are inextricably linked to and dependent on the forest where they get a significant portion of their food and exercise customary livelihoods practices—including Handep, an Adat philosophy of mutual assistance.

Ferdi Kurnianto, from the Ma’anyan Dayak tribe, and Director of the AMAN Central Kalimantan organisation—Indonesia’s largest Indigenous rights network—explains:

“In the constitution, land and forests belong to the people, the government is simply the regulator, not the owner. To faithfully implement its mandate, the government needs to pass regulations to grant territories and forests to Adat communities, but it isn’t doing so. Investors should only receive time-bound concessions, with land and forest ownership remaining with the Adat community. But the government and investors act like the owners.”

Indonesia Still Has No Indigenous Rights Law

Sandi Jaya Prima, a lawyer with the Central Kalimantan Legal Aid Foundation, known as LBH, noted that although the Indonesian Constitution recognises Adat communities and their traditional rights (art. 18), the legal framework to concretely make this happen is insufficient as Indonesia’s national Indigenous Peoples bill has been stuck in parliament for over 10 years with no progress in sight. The outgoing parliament twice introduced and then retracted the Indigenous rights legislation from the parliament’s agenda during their term. This has caused the recognition of Indigenous Peoples, their Adat territories and their forest/land tenure to be governed by confusing and contradictory set of regulations.

Indeed, Indonesia’s Ministry of Home Affairs published a regulation in 2014 to devolve the authority to recognise and protect Indigenous Peoples (including Adat territories) to provincial and regency authorities, subject to the passing of further local regulations by provincial and regency legislative bodies. Central Kalimantan’s parliament finally enacted a deeply flawed regulation in 2024 setting out the rules for Adat registration, though the law has yet to enter into force. Up until then, in this legal vacuum, only four Regency Governments had passed local regulations to recognise Indigenous Peoples and organise the registration of Adat territories. Only one regency has been approving Adat applications for the recognition of Indigenous groups and their territories in practice.

The coalition of Central Kalimantan Adat rights organisations has written to the Governor to contest the discriminatory nature of the new provincial legislation and its failure to address the root causes of the loss of Adat territory and culture. Many Indigenous groups and advocates believe the 10-year delay in passing the Indigenous Peoples bill is a deliberate strategy to prioritise the granting of investor rights over the rights of Central Kalimantan’s Adat communities.

At the Central Kalimantan Indigenous festival, Irene Natalia Lambung from Solidaritas Perempuan, a local branch of the Indonesian Women’s Solidarity network, highlighted how the presence of large investor concessions has gendered impacts that receive little attention. Women’s economic situations become especially precarious as they lose access to resources and areas their livelihoods depend on; transforming women from producers to consumers. Many have to emigrate in search of work or resort to under-paid, exploitative labour for companies neighbouring their communities, where they also face significant physical abuse. The presence of these new activities on previously forested land generates profound changes to Adat societies.

Strategies and ways forward

Given the current state of affairs, much bottom-up advocacy is needed. Essential to the strategies of the Central Kalimantan coalition is the promotion of spaces where community members can themselves voice their demands – an ingredient often missing in campaigns about Indigenous Poeples’ rights.

But Adat communities’ political power has been fragmented by their “criminalisation” when they contest investor control over their territories. In response, LBH has been defending Adat community members in court when they face unjust prosecution. AMAN has been supporting activities to revitalise customs, territories and cultures. YBBI and Solidaritas Perempuan have been investing in Adat livelihoods activities. Meanwhile, Save our Borneo raises public awareness of environmental and human rights issues through targeted communications. And WALHI conducts investigations to monitor company violations of the law, as well as analysis of the governance framework that underpins the granting of large-scale concessions to investors. These six organisations mutualising their efforts to create greater impact at the policy level in Central Kalimantan – but their endeavours need broader support.

International pledges don’t match local needs

Efforts to protect Indigenous Peoples’ territories and forests are increasingly being promoted under international frameworks, including the UN’s climate change and biodiversity agreements. While it is encouraging that governments are making commitments to recognise and protect Indigenous Peoples’ rights, even if belatedly and at times half-heartedly, the interest in securing Indigenous Peoples’ rights should not be limited to the role they play to mitigate the disastrous impacts the global economic system has on the environment. This conversation is about much more than reducing CO2 levels in the atmosphere, yet many international donors believe CO2 to be the best unit of measure to justify financial support for protecting Indigenous territories. Indonesia is a signatory of the 2021 Glasgow Pledge, which sets important targets for deforestation reduction and creates a US$1.7 billion funding package to strengthen Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ tenure rights to assist these efforts. As evidenced by the testimonies of Central Kalimantan Indigenous rights organisations, this cannot happen without a political shift in attitudes towards the rights of Adat communities; supported by legislation designed in a way that is participatory, inclusive and accountable to Indigenous communities.

This blog post was written in the context of the ALIGN project. ALIGN supports governments, civil society, local communities and other relevant actors in strengthening the governance of land-based investments. It is funded with UK aid from the UK government, however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of ALIGN partners or the UK Government.