Updated by Rick de Satgé. The content draws on the original profile prepared by Rosalie Kingwill in 2017. The new version has been reviewed by Ben Cousins, Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) at the University of the Western Cape

8 August 2021

In 2019 South Africa had a population of 58.5 million people. The country has a land surface area of 1,220,000 km². Of this, around 11% of the land is arable. There are significant ecological variations ranging from dry conditions (desert and semi desert) in the west to two bands of higher rainfall in the east.

By 2019 16.8% of households lived in informal dwellings across South Africa’s nine major metropolitan municipalities.

Somkhele Coal Mine, photo by Rob Symons/GroundUp (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

South Africa is considered to be a water scarce country, with this scarcity exacerbated by extreme social and economic inequality. Just 28% of the land surface receives 600 mm or more of rain per annum. This means that most of the land is suitable only for livestock or wildlife production

Historical backdrop

Agriculture in precolonial and early colonial society was primarily pastoral in nature. The South African countryside was transformed through centuries of colonial incursion from the middle of the 17th century, protracted border wars and conquest. The discovery of diamonds and gold in the 19th century attracted a growing European settler population. Mining-related economic growth created an enormous demand for labour, and black labour reserves were created to service the rapidly expanding economy. By the end of the 19th century the majority of land had been appropriated by settlers from the indigenous population. A strong, state-engineered and white-owned capitalist agricultural sector developed, supported by a combination of state subsidies and the regulation of agricultural commodity prices and markets1.

Throughout the 20th century numerous discriminatory laws and policies aimed at racialised forms of social engineering continued the dispossession of the black majority, and severely restricted their access to rural and urban land. The 1913 and 1936 Land Acts led to forced removals of hundreds of thousands of black South Africans and were reinforced by a battery of additional legislation during the apartheid era, which uprooted millions more and served to deepen the distortions in rural and urban landscapes.

The combination of discriminatory legislation and forced removals sought to bring about complete spatial and political segregation of the races. Africans were expected to reside in fragmented ethnic ‘homelands’ and ‘bantustan’ enclaves, constructed around ten colonially defined cultural-linguistic identities, and constituting around 13% of the total land area of the country. These homelands were largely controlled by pliant local elites, including many ‘traditional leaders’ and chiefs elevated through the colonial and apartheid systems. Rural reserves were also created for mixed-race people and indigenous Khoisan people (formerly hunter-gatherers), who in state parlance were generically referred to as ‘coloureds’. Urban areas were also strictly racially and spatially segregated with the first black townships established in the late 1920’s, a process consolidated under apartheid from the 1950’sm giving rise to what today is often referred to as the ‘apartheid city’.

By the early 1990’s something of a stalemate had developed in the bitter struggle for equal rights and political freedom for the majority. This forced parties to negotiate a settlement which formally ended apartheid rule in 1994. The transition to democracy took place in the context of a new and powerful neoliberal world order which constrained the possibilities for far reaching social change. In consequence, the deeply entrenched legacies of spatial and economic inequality have proved to be exceptionally difficult to dislodge. Although land dispossession was a key element driving popular struggle, today most of the land in South Africa remains owned by white people. Relatively large numbers of blacks and coloureds still live on white owned commercial farmland as workers, labour tenants or insecure occupiers, although increasingly many have been displaced off-farm2.

Land legislation and regulations

The Constitution of 1996 advocates a radical break from past patterns of land ownership. Section 25, known as the ‘property clause’, provides a constitutional imperative for all the land reform legislation and programmes that have followed. Section 25 contains subsections which protect property rights and specifies the circumstances under which land may be legally expropriated. Subsection 25(3) sets out a detailed set of criteria which must be taken into account in the determination of compensation. The clause as a whole hinges on the balance of public and private interests within land reform and determining just and equitable compensation.

Subsequent subsections bind the state “to take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to foster conditions which enable citizens to gain access to land on an equitable basis”; to pass legislation enable citizens to have tenure which is legally secure, while creating the right for those who were dispossessed of property after 19 June 1913 (corresponding with the passing of the 1913 Land Act) to claim “restitution of that property or equitable redress”. The property clause goes further, stating in Subsection 25(8) that “no provision of this section may impede the state from taking legislative and other measures to achieve land, water and related reform, in order to address the results of past racial discrimination”.

In recent years South Africans have been engaged in a debate as to whether or not to amend the Constitution to allow for expropriation of land without compensation (EWoC), in order to expedite land redistribution and restitution. These have proceeded very slowly over the past 27 years (see below). Critics argue that the Constitution already makes provision for expropriation at less than market value, and that the debate is a political diversion to mask political failures to realise the transformative power of the constitution to promote wide-ranging land reforms in the public interest.

All of us know that the problem is not with the constitution‚ the problem has been the failure to resolve the unresolved issues despite an enabling legal framework.

Tembeka Ngcukaitobi

A protracted, and as yet incomplete parliamentary and public process to consider amending the Constitution has seen political parties deadlocked on the wording of a possible amendment, and also the issue of whether or not the state should take ‘custodianship’ of all land. Following the publication of the Constitution 18th Amendment Bill in December 2019 Parliament received more than 200,000 submissions from the public3.

At the same time an Expropriation Bill [B23-2020] has been prepared to replace an outdated law from 1975. The Expropriation Bill distinguishes between expropriation for a public purpose and in the public interest. This is consistent with Section 25(4) of the Constitution which defines public interest as including the “the nation’s commitment to land reform and to reforms to bring about equitable access to all South Africa’s natural resources”4. There has been some confusion between the processes of amending the Constitution and the introduction of the Expropriation Bill, as “the former addresses the issue of expropriation without compensation while the latter sets out the procedures for how expropriation is to be done”5.

Overall, a wide range of legislation has been passed governing land issues. This is supplemented by numerous laws regulating environmental management, water, protected areas, national forests and fisheries.

Three land laws passed toward the end of the apartheid era remain on the statute books. Two of these allow for upgrading to, or maintenance of, titles: the Upgrading of Land Rights Act, 112 of 1991 (ULTRA) and the Land Titles Adjustment Act, 111 of 1993 (LTAA). The third – the Ingonyama Trust Act 3KZN of 1994 has been highly controversial. The Ingonyama Trust was established through a deal between the then ruling National Party and the Inkatha Freedom Party, concluded just hours before the democratic transition in 1994. The Trust was established to manage 2.8 million ha of land notionally owned by the former homeland government of KwaZulu, but in fact occupied by millions of people with customary rights to occupy and use the land. This land was vested in the Ingonyama, the Zulu King, as trustee on behalf of members of communities defined in the Act. The Act was amended in 1997 to create the KwaZulu-Natal Ingonyama Trust Board, which administers the land in accordance with the Act. (See the section on community land rights below for more information on recent developments.)

The table below highlights the key legislation passed to give effect to the obligations of Section 25 since 1994.

|

Redistribution: Section 25(5)

Tenure security: Section 25(6)

Restitution: Section 25(7)

|

The Restitution of Land Rights Act 22 of 1994 was among the first acts passed by the democratic parliament in South Africa. It provided that all land restitution claims had to be lodged by 31 December, 1998. However, the restitution programme has proved to be fraught with problems6. It has also been the subject of political manoeuvre under the Zuma Presidency7, as the land claims process was reopened through the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act 15 of 2014, which was hurriedly signed into law8. The claims lodgement period reopened on 1 July 2014 for a five-year period. This had the effect of jeopardising existing unsettled land claims lodged in the first phase9 of restitution, which became the focus of a court action. In June 2016, the Constitutional Court ruled that all land restitution claims made after December 1998 had to be put on hold, after finding that Parliament did not properly consult the public before passing the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act in 201410. Parliament was given 24 months from the date of the order to enact new legislation, while the newly lodged claims could not be processed or settled. This deadline was not met, and the Constitutional Court declined to approve an extension. This places all the land claims lodged in the second phase in a legal limbo.

The Commission on Restitution of Land Rights (CRLR) reported that by 31 March 2020, 81 782 land old order claims had been settled, resulting in the award of 3.7 million hectares of land to the beneficiaries of which 2.6 million hectares had been transferred. The CRLR reported that it currently has a total of 8 447 old order – backlog claims still outstanding11. Despite the official figures analysts argue that the Restitution programme has been “plagued by historical misconceptions”12– particularly those that assumed that land in precolonial times was owned by chiefs – and has delivered few tangible benefits to those who were dispossessed.

There has been no law passed to give effect to Subsection 25(5) which seeks to enable equitable access to land. To date South Africa has relied on amendments to older legislation passed in 1993 to give effect to the redistribution programme. The redistribution programme was premised on the principle of willing buyer – willing seller and has been through a number of iterations13.

The High Level Panel14 established under former President Kgalema Motlanthe prepared an indicative National Land Reform Framework Act which sought to put in place key land reform principles to “guide the interpretation, administration and implementation of all the relevant land reform laws passed since 1994” “and provide the general framework within which all land reform and post-settlement support plans are made and implemented. However, the recommendations of the Panel have not been implemented.

With respect to legislation fulfilling the mandate of Subsection 25(6) to promote tenure security, several laws have been passed.

The Land Reform Labour Tenants Act 3 of 1996 seeks to protect the rights of labour tenants living on land owned by others but who have, or have had, the right to use cropping or grazing land on a farm in exchange for their labour. Most labour tenants are found in KwaZulu–Natal, Mpumalanga and Limpopo provinces. It was estimated that by the end of the 1980s, there were around half a million individuals operating within some sort of labour tenant system15. However despite the passing of this Act, the department responsible for land reform failed to implement it. This failure was the subject of a class action in which the court ruled that the department was in breach of its constitutional obligations and ordered that a Special Master of Labour Tenants be appointed to process all unresolved claims.

Rural homestead, photo by John Flanigan (CC-BY-NC)

In the former bantustans (the ex- ‘homelands’) land administration is virtually non-existent. Apartheid-era Permission to Occupy certificates (PTOs) are still issued by some traditional councils, but very unevenly, and their current legal status remains unclear. With the dissolution of the bantustans, many land records have been lost or destroyed.

Legislative protection for the land rights of those living in the former bantustans is currently provided only by the Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act 31 of 1996 (IPILRA) which, as the name suggests, was intended to be a temporary law. It has to be renewed every year. There is widespread agreement that IPILRA has not been widely promoted or effectively enforced. This has made residents in the former homelands vulnerable to land grabs, particularly in relation to mining deals entered into between companies and chiefs.

IPILRA recognises and seeks to secure the undocumented rights of people who own or use land but has been almost universally ignored in the negotiation of mining rights on communal land16.

However, IPILRA has been used to halt mining and land appropriation in at least one part of the country17.

The Communal Land Rights Act 11 of 2004 ,which was intended to supersede IPILRA, evoked widespread resistance from rural people because it gave increased powers to traditional leaders and traditional councils (known as tribal authorities under apartheid), who were given sole responsibility to control occupation, use and administration of communal land18. The Act was finally struck down in its entirety in 2010, following a protracted legal battle which went to the Constitutional Court. This Act has yet to be replaced, although there are some indications that new legislation is currently under development.

The Traditional and Khoisan Leadership Act 3 of 2019, which came into force on 1 April 2021, has removed many of the protections provided by IPILRA. The TKLA replaces the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act of 2003 as the law recognising and regulating traditional leadership structures in South Africa. The TKLA has attracted great criticism:

The Act allows traditional councils to enter into partnerships or agreements with a third party without the need for consent from people who will be directly affected. This puts the land rights of communities and individuals at risk – effectively, a traditional council can sign a mining or development deal without the express permission of land right holders19.

The Extension of Security of Tenure Act 62 of 1997 was passed to protect the tenure rights and rights to family life of farm workers and dwellers living on privately owned land, mainly commercial farms. Since 1994, solutions for the complex challenges posed by efforts to secure both tenure rights and access to housing and services of those living on commercial farms have remained elusive. The DRDLR has acknowledged that the implementation of ESTA has collapsed under the weight of “total system failure”20.

Land restitution claimants and beneficiaries of the earlier land redistribution programmes where land was transferred in ownership could establish a legal entity to hold their land and manage their rights. Two types of entity have been commonly used – Communal Property Associations established in terms of the Communal Property Associations (CPA) Act 28 of 1996 and land-owning trusts established in terms of the Trust Property Control Act, 57 of 1988. However, it is widely acknowledged that these legal entities have been poorly supported by the state. The majority are not compliant with the requirements of the Act, and many have become vehicles to enable asset capture by elites.

The Transformation of Certain Rural Areas Act 94 of 1998 seeks to clarify and secure the land rights of the descendants of Khoisan people, who, following the legal abolition of slavery in South Africa in 1834, were settled around mission stations, or in declared reserves. There are 23 such rural areas in four provinces (Western Cape, Northern Cape, Eastern Cape and Free State). Currently this land is held in trust by the Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development. TRANCRAA enables land to be transferred to municipalities, or to a land-holding entity such as a Communal Property Association, controlled by the members. However, progress in this regard has been extremely slow.

Richtersveld community members, photo by Louis Reynolds (CC-BY-NC)

Occupants of the rapidly expanding informal settlements located in urban areas are protected against arbitrary eviction by the Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act (PIE) 19 of 1998. PIE was promulgated to do two things. On the one hand it sought to prohibit unlawful occupation of land, while on the other it put in place fair procedures for the eviction of unlawful occupiers who occupy land without permission21. (Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, all eviction proceedings have been suspended, although this is a temporary measure).

In March 2021 a Land Courts Bill was approved by Cabinet for submission to Parliament. This seeks to establish a specialist Land Court and a Land Court of Appeal, the former having the status equivalent to a high court and the latter equivalent to that of the Supreme Court of Appeal22.

While there is no shortage of legislation in South Africa, effective implementation remains a significant challenge. Officials tasked with land use and land reform planning are often poorly trained and resourced. At the same time “a strong culture of mandate protection (by different government departments) deepens institutional fragmentation and locks actors into specified roles, functions and responsibilities”23. A recent study on South Africa’s Land Data and Information Ecosystem notes that while government provides over 60% of available land data there is a need for “clear divisions and responsibilities when it comes to data custodianship between different government departments”24.

Land tenure classifications

Historic rights

The democratic state inherited the following broad categories of rights from the apartheid era:

- Strong registered rights of ownership (rural and urban) also sometimes referred to as 'freehold' title, under a rigorous system of deeds registration and surveyed cadastral boundaries, regulated mainly by the Deeds Registries Act 47 of 1937 and the Land Survey Act 8 of 1997.

- Evolving forms of title for urban blacks recognised as permanent residents, and a few rural blacks with historic title.

- Occupancy rights for blacks on communally held land in the former black reserves, held under a plethora of land proclamations (not Acts of Parliament).

- Insecure 'informal' tenure in township settlements.

Post-apartheid rights

The basic structure of immovable property law has remained largely unaltered, even though new legislation recognising the rights of those living on land owned by others as well as protecting those living on land in the former bantustans has gone some way to constrain the perceived unfettered power of registered rights.

There are six categories of registered rights:

Freehold: This provides for rigorously regulated ownership by juristic entities that may be individuals, corporations or trusts in rural or urban areas, and which allow for the rental of property.

State leasehold: This originated in a state scheme to provide 99-year state leasehold for black people with urban residence rights under the apartheid system. In the post-apartheid era, state leasehold is being promoted as an alternative to freehold. The State Land Lease & Disposal Policy enables emerging farmers and land reform beneficiaries to obtain a 30-year lease on state-owned land which is renewable for a further 20 years and may involve an option to acquire freehold ownership.

Leasehold title: This involves registering a notarial deed against the title of ownership by the lessor (the person letting the property) in favour of the lessee (the person to whom the property is let). The lessee gains rights over the property for a certain amount of time without that person becoming the owner but can exchange the right for compensation at market value.

Sectional Title: This applies primarily in urban apartment blocks or housing estates for middle class owners. It enables the creation of surveyed individual units under full ownership, with common property and corporate management. Sectional title schemes are regulated by the Sectional Titles Act 95 of 1986.

Communal Property Associations: The Communal Property Associations Act was promulgated to create a land holding entity to enable a group or community of black land reform beneficiaries to acquire, hold and manage property on a basis agreed to by members of a community in terms of a written constitution.

Quitrent title: This is a historic form of title phased out for conversion to freehold for whites a long time ago, and recently, but ineffectively, for blacks (mainly in the Eastern Cape) in terms of the Upgrading of Land Tenure Rights Act (ULTRA).

Off-register rights

The following table, based on a variety of research reports, provides an estimate of the population with unregistered rights:

Table 1: Land holding outside the formal property system in 201125

| Location | Number of people | % of the population in 2011 |

| Communal areas | 17 million | 32.8% |

| Farm workers and dwellers | 2 million |

3.9% |

| Informal settlements |

3.3 million |

6.3% |

| Backyard shacks |

1.9 million |

3.8% |

| RDP houses with no titles |

5 million |

9.6% |

| RDP houses with title issued but which no longer accurately reflect ownership |

1.5 million | 3.0% |

| Total |

30.72 million |

59.7% |

The numbers of people with off-register rights appear to be rising incrementally due to population growth and no significant advances in tenure reforms.

Land use trends

Sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing acute impacts of climate change. A recent World Bank report forecasts that by 2050 there will be 86 million climate migrants across the region26.

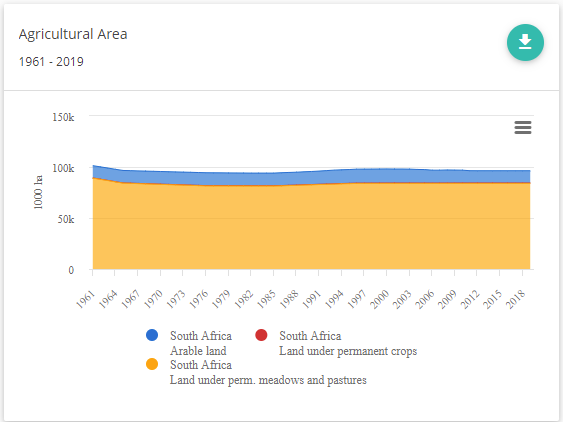

Source: South Africa Agricultural Area, FAOSTAT

In South Africa it is predicted that rainfall will be more infrequent but also more intense as a result of climate change. This will shrink the country’s arable land and increase agricultural unpredictability. Less than 3% of South Africa is considered high potential land, while 69% of the land surface is suitable only for grazing or wildlife. This makes livestock farming the largest agricultural sector in the country27.

Deregulation in the agricultural economy from the 1990’s, as the democratic government sought to reduce subsidies for white farmers, accelerated the trend toward large-scale intensive farming with a focus of the production of high-value export crops. This saw the emergence of ‘Big Food’ and the growing dominance of a few large vertically integrated corporations active along the entire value chain. The creation of the SAFEX futures market in key agricultural commodities has led to the financialisation of the sector28.

These trends have resulted in growing concentration in the agricultural sector, with many smaller producers unable to compete and going out of business. Smallholder agriculture remains poorly supported. Less than 0.5% of the national budget has been allocated to land reform, and land redistribution and agricultural support policies have privileged a small number of black commercial farmers.

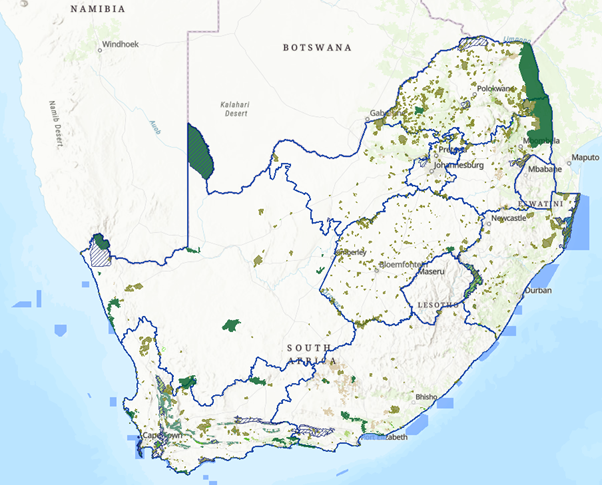

With respect to biodiversity management the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act (Act 57 of 2003) requires the Minister to maintain a Register of Protected Areas. South African legislation enables the creation of gazetted protected areas while conservation areas are managed for biodiversity conservation but are not legally declared.

Protected Areas in South Africa, map by Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment

Land investments and acquisitions

Local agribusiness in combination with global investors is expanding into other African countries. South African based farmland funds such as the Emvest Agricultural Corporation and the Old Mutual’s African Agricultural Fund, together with transnationalised banks, enable South African, UK and other investors to diversify their investments into African agriculture29. The geographic spread of these investments is wide, and is reported to include Angola, Botswana, DRC, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

However, this investment path has not been smooth and there have been significant failures where South African investors sought to develop land in the DRC and Mozambique.

Women’s land rights

Xolobeni farmer, Photo by Daniel Steyn/GroundUp (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Women and men have equal rights in terms of the South African Constitution. However, in practice this equality has been difficult to realise. It has been argued that “many of the most serious land-related problems facing women exist at the interface between distorted custom and past colonial and apartheid statute law”30. Everyday practice in different customary settings is leading to changes outside the statutory arena, as women renegotiate their rights to land.

The struggles over land rights that are underway in South Africa are inextricably bound up with struggles over the content of custom. They are not so much struggles against custom, but rather, contestation over the content of customary entitlements to land in the context of the equality rights guaranteed by the Constitution31.

These struggles take place in a policy and legislative context where it is argued that the state has distorted living customary law by empowering traditional leaders to unilaterally interpret custom. This can be seen in laws such as the TKLA, the Traditional Courts Bill and the Communal Land Rights Act, which was struck down by the Constitutional Court on procedural grounds. The latter was argued to have entrenched ‘old order’ conceptions of land being the exclusive property of the male household head32.

Access to land by unmarried women with children is an important issue, and there is evidence that customary law is increasingly recognising their claims33. In this regard arguments about the “values underlying customary systems (in particular the primacy of claims of need) and entitlements of birth right and belonging are woven together with the right to equality and democracy” to advance the legitimacy of these claims34.

Urban tenure issues

Around 11.7 million people who resided in urban areas in 2011 were estimated to have ‘off register’ and informal rights to land35. These constituted almost 23% of the total South African population. In 2016 approximately 1 in 7 South African households lived in an informal dwelling. By 2019 16.8% of households lived in informal dwellings across South Africa’s nine major metropolitan municipalities36.

Evictions in Khayelitsha, Photo by Brenton Geach/GroundUp (CC-BY-ND)

Extreme spatial inequality characterises South African urban settings37. Despite South Africa’s substantial progress in delivering subsidised housing38, much of this has been on the urban periphery. This has further entrenched the spatial segregation characteristic of apartheid spatial planning. As early as 2011 it was found that “close to half of the subsidised properties awarded to qualifying households in South Africa had not been registered, meaning that nearly 50% of housing beneficiaries did not yet have title to their subsidised properties”. This has raised two fundamental questions – whether South Africa’s costly and rigorous title deed registration system can work for the majority of the population and what a more appropriate ‘fit for purpose’ register of property rights might look like. Despite state policy intent, there is little evidence to suggest that state-subsidised housing, as some kind of asset for the poor, has any systematic ability to facilitate an exit from poverty39. It has become increasingly clear that urban poverty cannot be addressed by recourse to titling and home ownership40. For many households, access to well-located land closer to jobs and amenities is the key to urban livelihood security.

In recent years policy commitments have been made to advancing “spatial justice”. For example, spatial justice is the first development principle in the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act of 2013 (SPLUMA). However, in practice thoroughgoing measures to reshape South African cities have yet to inform spatial planning.

Urban precarity has been further amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic. In April 2020, after the imposition of a national ‘lock-down’, 61% of households in shack areas reported running out of money to buy food by the end of the month. This is aggravated by the fact that far fewer shack dwellers receive government grants41. Covid-19 has led to a further proliferation of informal settlements, as households lost jobs and livelihoods and were no longer able to pay rent in backyard dwellings.

Community land rights issues

Following the transition to democracy, South Africa’s former bantustans were incorporated into the nine provinces. It has been observed that while many South Africans resisted the imposition of Tribal Authorities under apartheid, both the Interim Constitution and the final 1996 Constitution recognised the institution of traditional leadership42. Despite a commitment to extending democracy, substantial concessions were made to institutions inherited from the pre-1994 era. The Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act and the Communal Land Rights Act (later struck down) had the effect of “effectively resuscitating the powers they enjoyed under the notorious Bantu Authorities Act of 1951”. More recently the passing of the Traditional and Khoisan Leadership Act has also been widely criticised for the continued retention of homeland boundaries, and the further augmentation of the powers and influence of traditional leaders, rendering 20 million rural South Africans as second-class citizens.

Civil society organisations have also expressed serious concerns that Section 24 of the recently promulgated TKLA enables traditional leaders to enter into deals which effectively sign away people’s land rights with minimal consultation. Section 24 enables traditional councils to conclude agreements with other traditional councils, municipalities, government departments and “any other person, body or institution”, including private developers and mining corporations.

As noted in the legislative section above, informal land rights in the former bantustans are protected by the IPILRA. “In terms of this Act if an informal land right is held individually, only the person who holds the right can consent to its deprivation. Where land is held on a communal basis, the decision to dispose of someone’s informal land rights can only be taken by a majority of all the land rights holders and is subject to local customary law”43.

Given that there are already several unlawful land and mining deals in traditional communities concluded even before the TKLA came into force, suggests that the political will to enforce IPILRA has been absent.

There is now a real risk “that traditional authorities and developers proceed as though consent is no longer needed before finalising an agreement that affects informal land rights. This uncertainty places rights holders within traditional communities in an incredibly vulnerable position and potentially threatens their homes, crop fields and grazing lands”44.

With regard to the Ingonyama Trust, a recent court judgment has declared that people living on customary land in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, notionally held in trust by the Ingonyama (king) of the Zulu people, are the “true and beneficial owners” of that land. The court found that the conversion of customary rights into leasehold requiring rights holders to pay rental to the Trust was illegal. The judgment as a whole has major implications for communal land tenure policy in South Africa, which it is argued must delimit the powers and functions of traditional leaders with regard to land and make them accountable to the rights holders45.

Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Tenure (VGGT)

In South Africa awareness raising around the VGGT was first undertaken in 2014 and a follow up blended training programme took place in 2015. Further workshops took place in 2016 bringing together a small group of participants from civil society organisations, social movements, private sector, academics, traditional leaders and government.

In late September 2017, a national Multi-Stakeholder Platform (MSP) was established, being co-chaired by the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR) and the Association for Rural Advancement (AFRA), to ensure VGGT related activities merge into a single approach to strengthen tenure governance, especially for the marginalised and vulnerable groups. Civil society organisations involved in the MSP establishment process took the decision to organise themselves into a national network, called LandNNES, to ensure that civil society is strengthened and able to participate effectively in policy level engagements with government and other actors in the MSP to strengthen land governance and land rights in South Africa.

Timeline – milestones in land governance

Late 19th century – By the end of the 19th Century whites had alienated much of the land in South Africa. Only 20% of the land which Africans had effectively used was retained as Reserve areas.6

1912 – Land Bank established to assist white farmers.

1913 – The Natives Land Act demarcated 77% of land for private ownership by whites and white owned companies.

8% was reserved solely for African occupation.

13% was reserved as Crown Land for game reserves, forests and other uses.

1923 – Native Urban Areas Act.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century the number of black people on rural land owned by whites increased rapidly. In the 1936 census 37% of the total African population were counted on farms, 45% in Reserves and 17% in towns.”

1927 – Black (Native) Administration Act was used extensively to authorise forced removals.

1936 –The Development Trust and Land Act made provision for the purchase of 6.2 million hectares of ‘released land’ from white farmers in areas adjacent to the areas scheduled for black occupation.

1950 – The Group Areas Act reserved areas for groups segregated by race.

1951 – The Bantu Authorities Act allowed for the creation of traditional tribal, regional and territorial authorities initially run by the Native Affairs Department and contributed to the fundamental distortion of customary law.

1960-1980 – Between 1960 and 1980 forced removals contributed to a massive population concentration in the bantustans, from 4.5 million to 11 million people. In the 1980’s 60,000 white commercial farmers owned 12 times as much land as the 14 million rural poor.

1993 – The Provision of Land and Assistance Act passed in the last year of the apartheid era provides the basis for land redistribution. The Act has been amended but not replaced.

1994 –Transition to democracy in South Africa

The Restitution of Land Rights Act provides the basis for a programme of land restitution.

1995 - 2000 A new suite of land policy and law passed including:

The Land Reform (Labour Tenants) Act

The Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act

The Extension of Security of Tenure Act (1996) passed in a bid to secure the tenure of farm dwellers

The White Paper on South African Land Policy (1997)

Legislation to regulate land occupations and evictions in urban areas

2003 – The Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act grants official recognition to traditional councils

2004 – The Communal Land Rights Act is passed before being struck down in 2010

2013 – The Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act puts in place key principles to guide land use planning. It gives municipalities the responsibility to determine land use decisions within their boundaries.

2014 –Land claims reopened until Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act sent back by Constitutional Court

2017 – The High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change appointed by Parliament makes extensive land related recommendations which remain unimplemented.

2018 – Public hearings commence on the need to review Section 25 of the Constitution

2019 – The Presidential Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture publishes its report

An Ad Hoc Committee established to Initiate and Introduce Legislation amending Section 25 of Constitution with respect to the expropriation of land

In December the Committee published the Constitution Eighteenth Amendment Bill.

Where to go next?

The author’s suggestion for further reading

There is an enormous body of research on land related issues in South Africa. The website of the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies has published extensive research related to land, agriculture, poverty, natural resource management, fisheries and food systems. It is possibly the richest resource on South African rural land issues available.

The Land and Accountability Research Centre also provides extensive resources with a particular focus on the recognition and protection of rights and living customary law in the former homeland areas of South Africa.

The Society, Work and Politics Institute has a land, labour and life research stream and has published important work on land rights and mining.

The Centre for Environmental Rights focuses on environmental law and produces a wide range of reports on mining, community rights and environmental impacts.

In the urban space the Socio-Economic Rights Institute is involved in applied research as basis for advocacy and litigation. This includes a focus on informal settlements and spatial inequality.

For coverage of land related news Phuhlisani NPC curates knowledgebase.land which collects links to news stories across a wide range of categories.

For an assessment about the state of land information in South Africa - how open and accessible land information is - please check the SOLI report for this country published by the Land Portal.

***References

[1] Hall, R. and B. Cousins (2015). Commercial farming and agribusiness in South Africa and their changing roles in Africa’s agro-food system. International conference: Rural transformations and food systems: The BRICS and agrarian change in the global South 20-21 April 2015, BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS).

[2] ILO (2015). Farm Workers’ Living and Working Conditions in South Africa: key trends, emergent issues, and underlying and structural problems. Pretoria, International Labour Organisation

[3] Public hearings were discontinued following the outbreak of Covid-19.

[4] Coetzee, J. and J. Marais. (2021). "Unpacking the who, what and why of the Expropriation Bill." Fasken Bulletin Retrieved 20 February, 2021, from https://www.fasken.com/en/knowledge/2021/01/28-unpacking-the-who-what-and-why-of-the-expropriation-bill/

[5] Parliament of South Africa (2020). The Expropriation Bill [B23-2020].

[6] de Satgé, R., D. Mayson and B. Williams (2010). The poverty of Restitution? The case of Schmidtsdrift. Overcoming inequality and structural poverty in South Africa: Towards inclusive growth and development. Birchwood Hotel, Phuhlisani.

[7] Hall, R. (2013). "‘What the one hand giveth, the other hand taketh away’: The Restitution Amendment Bill and new conditionality on restoring land to claimants." Another Countryside http://www.plaas.org.za/blog/%E2%80%98what-one-hand-giveth-other-hand-taketh-away%E2%80%99-restitution-amendment-bill-and-new-conditionality Accessed 23 July 2013.

[8] Cousins, B., R. Hall and A. Dubb. (2014). "The Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act: What are the real implications of reopening land claims?" Policy brief 34 Retrieved 20 October, 2014, from http://www.plaas.org.za/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/Policy%20Brief%2034%20Web.pdf.

[9] Cousins, B. (2016). "Land reform is sinking. Can it be saved?" Retrieved 15 March, 2020, from https://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files/Land__law_and_leadership_-_paper_2.pdf.

[10] Genesis Analytics. (2014). "Performance and Expenditure review: Land Restitution Postscript." Retrieved 12 June, 2021, from https://www.gtac.gov.za/perdetail/7.1%20Summary.pdf.

[11] CRLR (2021). Annual performance plan 2021-2022. Pretoria.

[12] HLP (2016). Report of Working Group 2 on Land Reform, Redistribution, Restitution and Security of Tenure. Roundtable 4 “Land Restitution”, High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change.

[13] Mayson, D. and R. Eglin (2018). Land Redistribution in South Africa 1994 -2018. Land Knowledge Base: Review Paper, Phuhlisani NPC.

[14] The High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change

[15] Cowling, M., D. Hornby and L. Oettlé (2017). Research Report on the Tenure Security of Labour Tenants and Former Labour Tenants in South Africa: . Commissioned report for High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change, an Initiative of the Parliament of South Africa, Parliament of South Africa.

[16] Manona, S., R. Kingwill, R. Eglin and S. Mtwana (2018). Land Tenure Review: Land Knowledge Base Review Paper, Phuhlisani NPC.

[17] In 2018 the case of Baleni and others v Minister of Mineral Resources and others tested whether mining licences could be issued without the consent of the Xolobeni community in Umgungundlovu in the Eastern Cape, whose rights to occupy the land are protected under IPILRA. The Judge ruled that the Department of Mineral Resources DMR was required to ensure that the processes set out in IPILRA were followed before a mining right could be issued.

[18] Customed Contested. (2013). "Communal Land Rights Act (CLaRA)." from https://www.customcontested.co.za/laws-and-policies/communal-land-rights-act-clara/.

[19] Custom Contested (2020) Traditional and Khoisan Leadership Bill (TKLB) https://www.customcontested.co.za/laws-and-policies/national-traditional-affairs-bill/

[20] Phuhlisani NPC (2016). Tenure security of farm workers and dwellers: 1994 - 2016: Commissioned report for High Level Panel on the assessment of key legislation and the acceleration of fundamental change, an initiative of the Parliament of South Africa, Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies.

[21] Moolla, M. (2016). "Having a slice of PIE – understanding the Act." De Rebus 24.

[22] Horn, M. and A. L. September-Van Huffel. (2021). "Land Court Bill: A step in the right direction for land reform." Retrieved 1 August, 2021, from https://www.ufs.ac.za/templates/news-archive/campus-news/2021/april/land-court-bill-a-step-in-the-right-direction-for-land-reform.

[23] Gelderblom, C. and N. Oettle (2020). Transformative cross-sectoral extension services dialogue: 2-3 March 2020 Synthesis Report Cape Town, Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, WWF, South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) and SA-EU Strategic partnership - The Dialogue Facility.

[24] May, L., C. Tejo-Alonso, M. Napier, A. Rosenfeldt and A. Cooper (2020). State of land information in South Africa, Land Portal and the Council for Industrial and Scientific Research (CSIR). P.7

[25] Hornby, D., R. Kingwill, L. Royston and B. Cousins (2017). Untitled: securing land tenure in urban and rural South Africa, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

[26] Mbiyozo, A.-N. (2021). "African cities must prepare for climate migration." Retrieved 1 August, 2021, from https://issafrica.org/iss-today/african-cities-must-prepare-for-climate-migration.

[27] WWF (2009). Agriculture: Facts and trends in South Africa, World Wildlife Fund.

[28] Hall, R. and B. Cousins (2015). Commercial farming and agribusiness in South Africa and their changing roles in Africa’s agro-food system. International conference: Rural transformations and food systems: The BRICS and agrarian change in the global South 20-21 April 2015, BRICS Initiative for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS). P 3

[29] Ibid.

[30] Mnisi, S. and A. Claassens (2009). "Rural women redefining land rights in the context of living customary law." South African Journal on Human Rights 25(3): 491-516. P 492

[31] Ibid. P. 494

[32] Nhlapo in Mnisi, S and A Claassens (209)

[33] Cousins, B. (2011). Imithetho yomhlaba yaseMsinga: The living law of land in Msinga, KwaZulu-Natal. Research Report 43. Cape Town, Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies.

[34] Mnisi, S. and A. Claassens (2009). "Rural women redefining land rights in the context of living customary law." South African Journal on Human Rights 25(3): 491-516. P. 500

[35] Hornby, D., R. Kingwill, L. Royston and B. Cousins (2017). Untitled: securing land tenure in urban and rural South Africa, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

[36] Statistics South Africa (2019). General Household Survey. STATISTICAL RELEASE P0318.

[37] Turok, I., A. Scheba and J. Visagie (2017). Reducing Spatial Inequalities through Better Regulation: . Report to the High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change., Human Sciences Research Council.

[38] Shisaka Development Management Services (2011). Investigation into the delays in issuing title deeds to beneficiaries of housing projects funded by the capital subsidy. Johannesburg, Urban Landmark.

[39] Budlender, J. and L. Royston (2016). Edged Out: Spatial mismatch and spatial justice in South Africa’s main urban centres. . Johannesburg, Socio-Economic Rights Institute (SERI).

[40] de Satgé, R., K. Cartwright, L. Royston, R. Kingwill and F. Mtero (2016). The role of land tenure and governance in reproducing and transforming spatial inequality. Commissioned report for High Level Panel on the assessment of key legislation and the acceleration of fundamental change, an initiative of the Parliament of South Africa. Unpublished, Phuhlisani NPC.

[41] Turok, I. and J. Visagie (2021). "COVID-19 amplifies urban inequalities." South African Journal of Science 117.

[42] Ntsebeza, L. (2005). Democracy compromised: Chiefs and the politics of land in South Africa. Leiden, Koninklijke Brill NV.

[43] de Souza Louw, M. (2021). "How the Traditional and Khoi-San Leadership Act promotes unlawful land deals." Customary law and institutions - Protecting or undermining community land rights in Southern Africa? https://landportal.org/debates/2021/online-discussion-customary-law-and-institutions-protecting-or-undermining-community 2021.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Cousins, B. (2021). "What landmark Kwazulu-Natal court ruling means for land reform in South Africa." The Conversation https://theconversation.com/what-landmark-kwazulu-natal-court-ruling-means-for-land-reform-in-south-africa-162969 2021.

Authored on

08 October 2021