We meet Rosalía in a roadside café in a dusty town in the Quiché department, in Guatemala’s Western Highlands. She lowers her voice whenever people come in – you never know who might be listening. Land is sensitive stuff, especially in Quiché, a region that still bears, perhaps more than any other part of Guatemala, the scars of the civil war (1960-1996) – as we will see. In 2018 alone, 15 defenders of land rights in Guatemala have been killed with total impunity, several of them in Quiché.

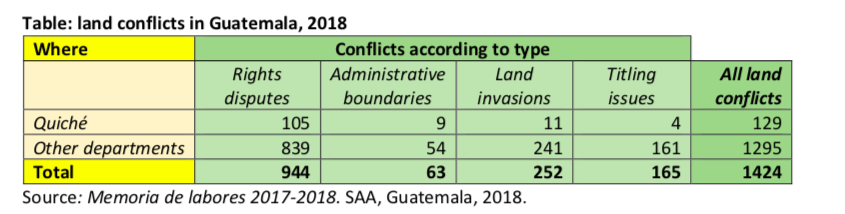

Before addressing ‘the troubles’ in the Quiché village of San José Sinaché, let’s take a look at some available data on Guatemala. Rather than consulting worldwide databases, we turn to information that is collected in the country, documenting that there is a constant amount of about 1500 ‘active’ land conflicts in Guatemala, 450 of which are solved each year. All cases are registered and monitored by the government’s Department for Agrarian Affairs (SAA). Although the dataset as such is not online, it constitutes the basis for analysis in the SAA Annual Reports.

Many of these disputes have to do with, sometimes violent, inter- and intra-community disputes –Guatemalan society is harsh and polarised. Earlier this year, two people died in confrontations between inhabitants of two municipalities in the Sololá department, over a territorial issue that goes more than a century back. One can only hope that the conflict in Quiché, one of the 105 rights disputes in the above table, fares better, but Rosalía is not so sure.

She tells us that the finca (estate) of San José Sinaché, with an area of 1,500 ha, has been the property of the Rivera family for as long as anyone can remember, with some 200 families of small farmers allowed to live and work on the property in return for part of their harvest: the so-called sharecropping system. The problems started when, a few years ago, the owners wanted to get rid of the estate, and the peasants started to look for ways to become the owners.

In the end, the finca was sold, but at the cost of severe and perhaps irreparable division in the community: a significant minority thinks that they should not have to pay at all for the land. Why not? Because, so they argue, for many years they and their ancestors have worked the sugarcane plantations of the Riveras near the Pacific coast in Escuintla, under a form of forced labour known as debt peonage; their only remuneration was the sharecropping arrangement in the Quiché estate. Thus, they refused to participate in the transaction. The other campesinos however went ahead, got a bank loan and bought the land in August 2018. Subsequently they were accused by the non-buyers of treason, and of intimidation, death threats included, to make them accept the deal and pay their part. In turn, the brand-new owners claim that the holdouts are now invading additional land on the estate.

But there is more to this than principles versus pragmaticism. The holdouts are being actively supported by the Comité de Unidad Campesina (CUC), a peasants’ union that has its roots in one of the former guerrilla movements. According to Rosalía, the non-buyers are relatives and descendants of (mostly Maya) villagers and farmers that, because of their CUC affiliation, were ruthlessly killed during the genocidal years of the civil war. The pragmatists, on the other hand, have connections to, or even used to be, members of the Civil Patrols: the vigilantes who did, precisely, the killing. For them, the prominent involvement of the CUC is hard to swallow, just like their own Civil Patrol background does not go down well at all with the holdouts. Danger looms: civil war wounds do not heal easily within Guatemalan communities, and little is needed to set them suppurating again, which is why Rosalía strongly advises against our visiting the area.

But there is more to this than principles versus pragmaticism. The holdouts are being actively supported by the Comité de Unidad Campesina (CUC), a peasants’ union that has its roots in one of the former guerrilla movements. According to Rosalía, the non-buyers are relatives and descendants of (mostly Maya) villagers and farmers that, because of their CUC affiliation, were ruthlessly killed during the genocidal years of the civil war. The pragmatists, on the other hand, have connections to, or even used to be, members of the Civil Patrols: the vigilantes who did, precisely, the killing. For them, the prominent involvement of the CUC is hard to swallow, just like their own Civil Patrol background does not go down well at all with the holdouts. Danger looms: civil war wounds do not heal easily within Guatemalan communities, and little is needed to set them suppurating again, which is why Rosalía strongly advises against our visiting the area.

The San José Sinaché case is an example of how, especially in Guatemala, land is an issue that cannot be understood if history is ignored. And not just recent (civil war) history: many conflicts in the SAA database are not very different from the ones caused by the arrival in 1524 of the Spanish troops led by Pedro de Alvarado. They simply grabbed (!) the land from the Maya, who were subsequently forced to work on it. Laws passed in the 19th century by the non-Maya elite had essentially the same effect, coercing the indigenous population into debt peonage regimes just this side of slavery. And although a century later Guatemala signed every conceivable international convention against forced labour, the phenomenon is far from eradicated. Against this background, the figure of 1400 land conflicts does not even seem that high.

Meanwhile, negotiations have been conducted, but in vain. In April 2019, Rosalía informs us that, after a meeting between the parties in February, a follow- up encounter was cancelled, which means the case will now probably go to court – if nothing ugly happens. Polarisation is far from over in Guatemala... but law suits are to be preferred over death threats.

This story was submitted as part of our recent Data Stories Contest and was the recipient of the third prize. Please note that names have been changed for confidentiality purposes.